Patience Pays Off: The Rewards of Tsai Ming-Liang’s Your Face

Your Face (Ni De Lian, 2018), the latest work from Taiwanese auteur Tsai Ming-Liang collects 13 extreme close-ups of faces that, together, tell stories of familial anguish, the consequences of prosperity and the inevitability of age. The film might challenge some audiences with shots as long as ten minutes, but Your Face doesn’t punish its viewers when their focus drifts. Instead, Tsai eases our gaze back to the screen by gently signalling our attention with the sparse and percussive score from composer Ryuichi Sakamoto (The Last Emperor, 1987; The Revenant, 2015).

Tsai’s stillness aligns him with other great filmmakers of what has been labelled Slow Cinema: Ozu Yasujirô’s painterly shot composition in films like 1953's Tokyo Story (MIFF 2016), or Chantal Akerman’s moving depictions of her mother in No Home Movie (MIFF 2016). Tsai’s sustained shots of faces capture a similar elongation of cinematic time, allowing him to amplify his subjects’ meditations and draw out their intergenerational angst, cynicism and hope. These long takes also reward audiences with unique insights into contemporary socio-political dynamics in Taiwan. These faces speak to the strain on the relationship between Taipei and rural areas, as well as the pressures and expectations of a successful career and the threat they pose to a strong and deep connection to family.

Slow Cinema, which Andrew Russell describes as “…[a] use of static shots, long duration shots, pans, tracking shots – as well as a narrative focus on the more mundane aspects of life” has long offered an alternative to the high-intensity, increasingly fast-paced filmmaking influence of Hollywood. Stillness is an antidote to nanosecond average-shot-lengths and invites a different but deeply rewarding kind of viewing experience. Ironically, the catalogue of Slow Cinema filmmaking has grown rapidly in recent years, as more films attempt to contend with the urgency of commercial releases. Slow Cinema is concerned with time and how we experience it. Your Face explores this filmmaking tempo in an explicit way: Tsai designs lengthy shots of faces to comment on the despair and pleasure associated with growing old. Some of the 13 subjects verbally address their bodies’ frailty and inadequacy. Others relish in the mundane, trying to stay awake or breathe clearly and regularly. Your Face takes the concept of Slow Cinema to its extreme. It's a glacially slow film that uses its unhurried pace to offer a treatise on the relentless decay of age.

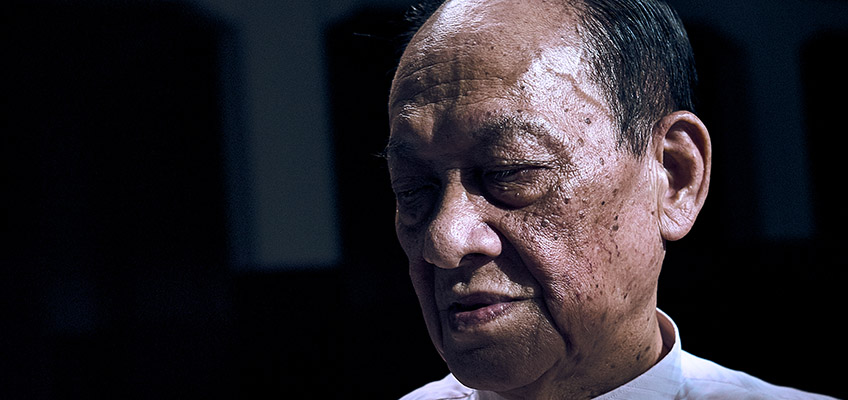

A scene from Your Face

The subjects (five women and eight men), unnamed until the final credits, are all middle-aged or older, but even the youngest of the faces are fixated on their desire to memorialise the past. While most of the characters are without dialogue, those that do speak tell stories of deflated romances and family struggle. The eleventh face, Ho Shu-Li, recounts the uncomfortable history of her affluence. Her migration to Taipei from a small town comes at the expense of a close relationship with her late parents. Ho begins to cry as she reminds herself about the opening of a high-speed railway between her rural hometown and Taipei. This train becomes her first opportunity to see her parents regularly in the last years of their lives, without compromising on the demands of her career. This sequence recalls Tsai’s debut feature Rebels of the Neon God (1992), which is deeply concerned with the tension between the corporate culture of Taipei and young people maintaining relationships with their families, a theme that echoes Ozu’s Tokyo Story. The high-speed railway exists as a technology at odds with the hyper-slow pace of the film. Tsai evokes the experience of time slipping away as Ho, much like the many other faces in the film, expresses her own grief about life being finite.

To produce these moments of vulnerability Tsai implemented a two-stage shooting process for his subjects who were steet cast, except for famous Taiwanese actor Lee Kang-Sheng (What Time Is It There, MIFF 2002; Stray Dogs, MIFF 2014). He first asked them to speak for thirty minutes about a subject of their choosing, and then requested that they sit silently, allowing them to do whatever they liked as he kept the camera rolling.

A scene from Your Face

Your Face encourages an interrupted and participatory kind of engagement with its audience and approaching the film as an artwork helps illuminate some of the ways this viewing experience functions. Much like painting, a practice which Tsai has cited as intrinsically linked to his filmmaking, the unbroken extreme close-ups of Tsai’s film invite us to run our eyes over the entire picture. Tsai’s parallel career as a video artist situates him in the company of other multi-skilled filmmaker-artists like Steve McQueen (Hunger, MIFF 2008), whose video artworks like Deadpan (1997) similarly invite carefully scanning the whole image. In Your Face our eyes creep up and around the frame, noting the dark shapes, floorboards and natural light diffused through old windows that Tsai used to frame his subjects. The shooting location for the film is the famous Zhongshan Hall, which celebrates its 83rd birthday this year and is also the subject of the Tsai’s excellent short film Light (2018), which is paired with MIFF’s screening of Your Face.

Tsai is not interested in traditional forms of cinemagoing that ask us to expend energy trying to suspend our disbelief. His 2003 narrative film Goodbye, Dragon Inn (MIFF 2004), which is set in a theatre that is literally crumbling, flags his interest in the cinema as a space not of attentive viewing, but of distraction and social interaction. In Goodbye, Dragon Inn characters mope around the movie theatre, vacantly staring at one another and fighting boredom. In Your Face, Tsai has developed this commentary on the space of the cinema through extreme close-ups of faces that enlist our ability to be lightly engaged, although now we are asked to consider and notice our own social environment. The film is as much about the subjects as it is our experience of watching them. In one sequence Lee Liu Chin-Hua explains, as she massages her cheeks and forehead, and flaps her tongue that “old folks need to exercise their [faces]… so they won’t stammer when they speak.” The room, in that moment, is full of audience members involuntarily mirroring her actions – touching their own faces. By triggering this involuntary reaction in the audience, Tsai creates a shared and embodied social experience.

Tsai asks us to become comfortable with patient contemplative viewing in a world of speed and urgency. These faces are stories of complex and difficult lives, and elderly figures attempting to accept that their bodies cannot perform as they once did. The passing of time is oppressive and relentless, and yet, here it is still, slow and deeply enjoyable.

Tsai Ming-Liang's Your Face plays the 2019 Melbourne International Film Festival on 10 and 14 August.